27 September 2024

Theo Meslin, Senior Sustainability & Energy Consultant

A question we often get from our clients is, “when can an asset be classified as Net-Zero?” This question, although seemingly straightforward, can become rather convoluted to answer, especially if embodied carbon emissions (emissions linked to the lifecycle of materials and the building), are considered. This is until the recent development of the UK Net-Zero Carbon Building Standard (NZCBS) [1], which finally brings a unified approach to assessing if a development can indeed be called “Net-Zero”. The standard entered into its pilot phase this week, where it will be tested, and feedback will be gathered to further improve it. We are yet to see if the proposed methodology and the (much-needed) emission and performance limits are to be embraced by the building industry.

The development of this standard is the result of a collaboration between some of the biggest players in the UK’s built environment: the Better Building Partnership (BBP)[2], the UK Green Building Council (UKGBC) [3], and many more contributors from the private sector including Longevity’s own CIO Ed Wealend, alongside Senior Consultant Sofia Narro Vallejo.

How is this standard different from previously issued guidance on carbon?

There are a few distinctions:

1. A collaborative effort:

The standard is the result of a uniquely collaborative effort between industry bodies involved in the decarbonisation of the UK’s Built Environment. This provides a single source of truth for what can be considered “Net-Zero”, one that has been approved by all of the most important stakeholders. This is a great advantage, especially when considering that many of these groups have previously developed their own methodologies, guidelines, or targets for operational and/or embodied carbon.

2. A combined view of carbon:

The UKNZCBS is also unique in that it looks at both operational and embodied emissions when determining if a building meets the requirements for a “Net-Zero” classification. While this is the case in other methodologies, such as the RICS methodology for assessing Whole-Life Carbon [4], the UKNZCBS is the first standard in which clear limits have been set for a wide range of asset types, for both operational and embodied emissions.

3. Measured approach:

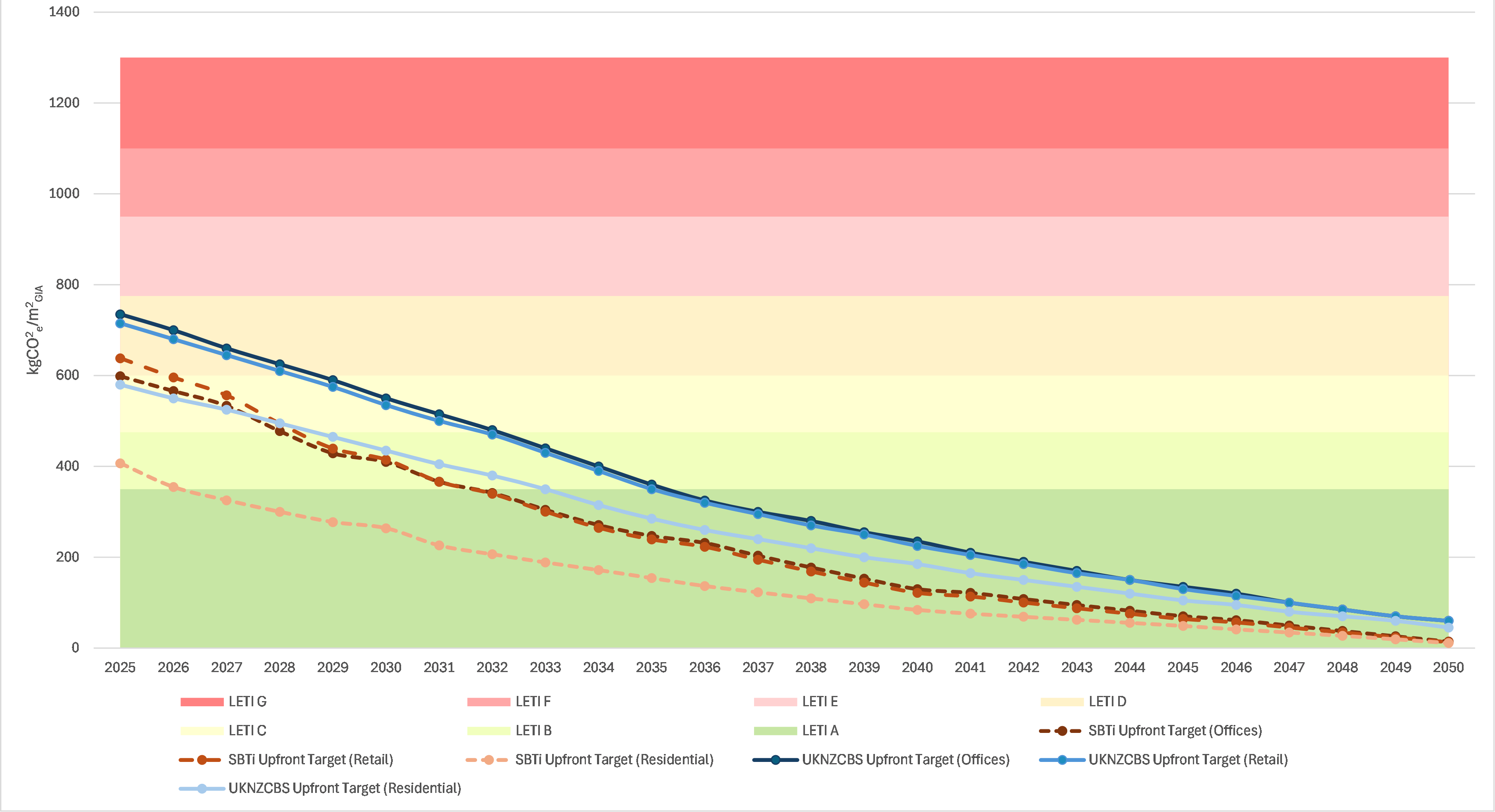

It is not the first time that reference data has been used to estimate targets and limits on carbon, but the UKNZCBS is undoubtedly the most up-to-date and complete version of this exercise and includes projected emission limits up to 2050. A substantial amount of work has gone into developing these operational and embodied emission limits for various typologies of buildings in order to acknowledge the fundamental differences between asset types. This can be seen for upfront carbon limits below, displayed in comparison with the LETI Rating limits for upfront carbon (office buildings), as well as the Science Based Targets initiative (SBTi) upfront carbon targets for office, retail, and residential buildings. For reference, LETI produced these banded performance limits to propose an equivalent to the Energy Performance Certificate (EPC) rating, but for embodied carbon. As for the SBTi limits, these were released in 2023 to offer an embodied carbon budget for the construction industry based on its contribution to our world’s overall carbon budget.

Figure 1: Upfront Carbon values – UKNZ

CBS[5] limits and SBTi[6] targets against LETI[7] rating limits (office buildings)

It can be noted here that the UK NZCBS limits for upfront carbon, while not as stringent as the SBTi targets for upfront carbon, are reducing at an equivalent rate. This is because these limits were set using a combination of a bottom up, model based on “what is theoretically possible” and a top-down carbon budget based on “what is necessary” approach. It must also be mentioned that the limits to be designed against will be for the year when the asset’s construction begins, making compliance with the standard’s requirements even more challenging. In the 2030s for example, when upfront carbon limits will be at or below 300kgCO2e/m2, compliance will require the implementation of a wide array of low-carbon materials, highly efficient design, and significant building product re-use.

4. Real results:

A key element of this standard is that, while it can be used during the design stage to guide performance, a project can only be certified “Net-Zero” once it has been completed. This means that any “Net-Zero” certified building will have achieved this through real and measured performance data, and not based on any predicted performance value. It is also the case that existing buildings can be certified as “Net-Zero” as long as the required information is available.

What does this all mean for the real estate industry?

In short, this standard allows developers and asset managers to more accurately assess if an asset is in alignment with broader climate objectives, for all sectors and scopes in the UK market. The hope is that most developments would aim to comply with this standard going forward, pushing design teams to seriously work on tracking (and reducing) their embodied carbon and designing their buildings to have highly efficient energy performance in-use.

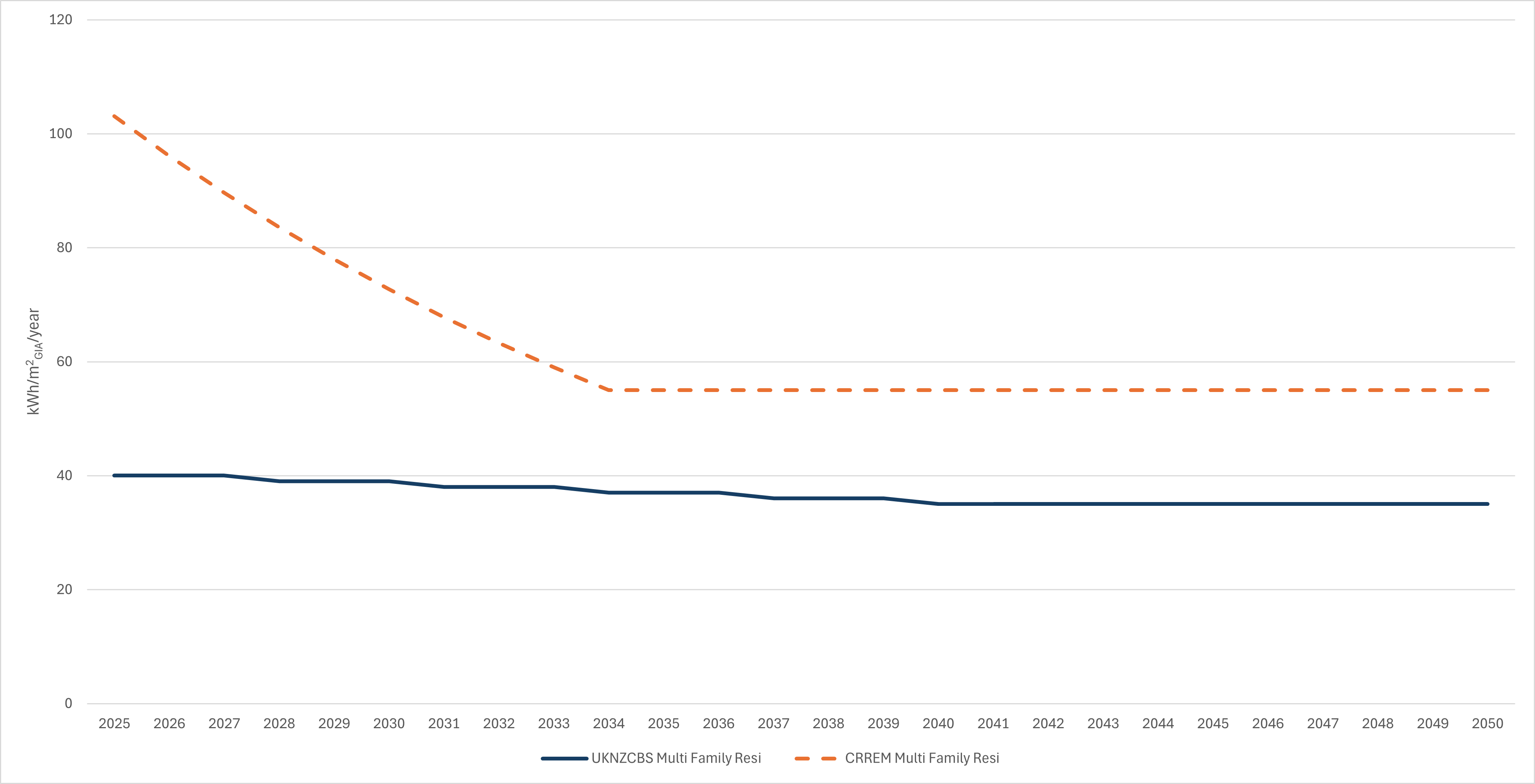

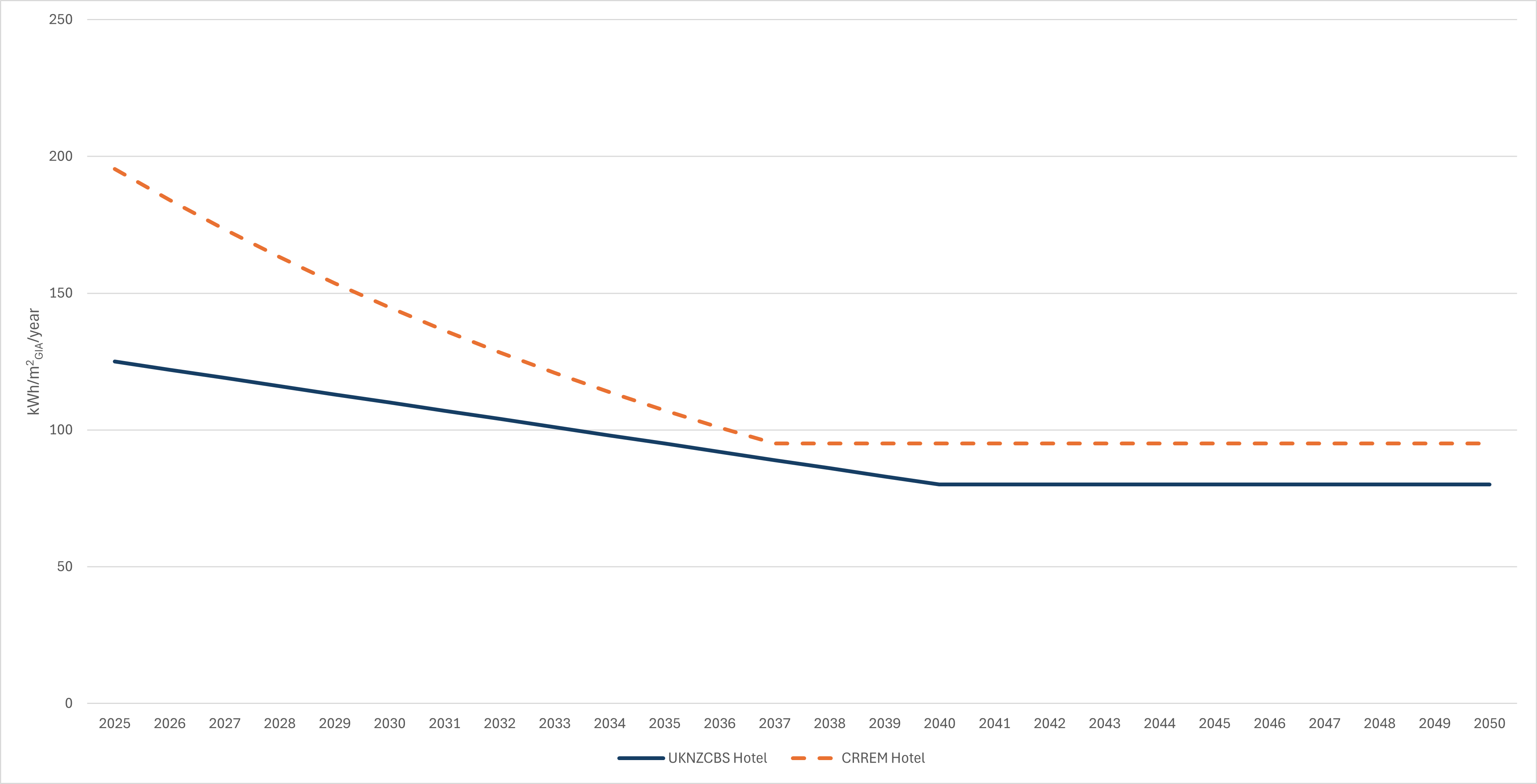

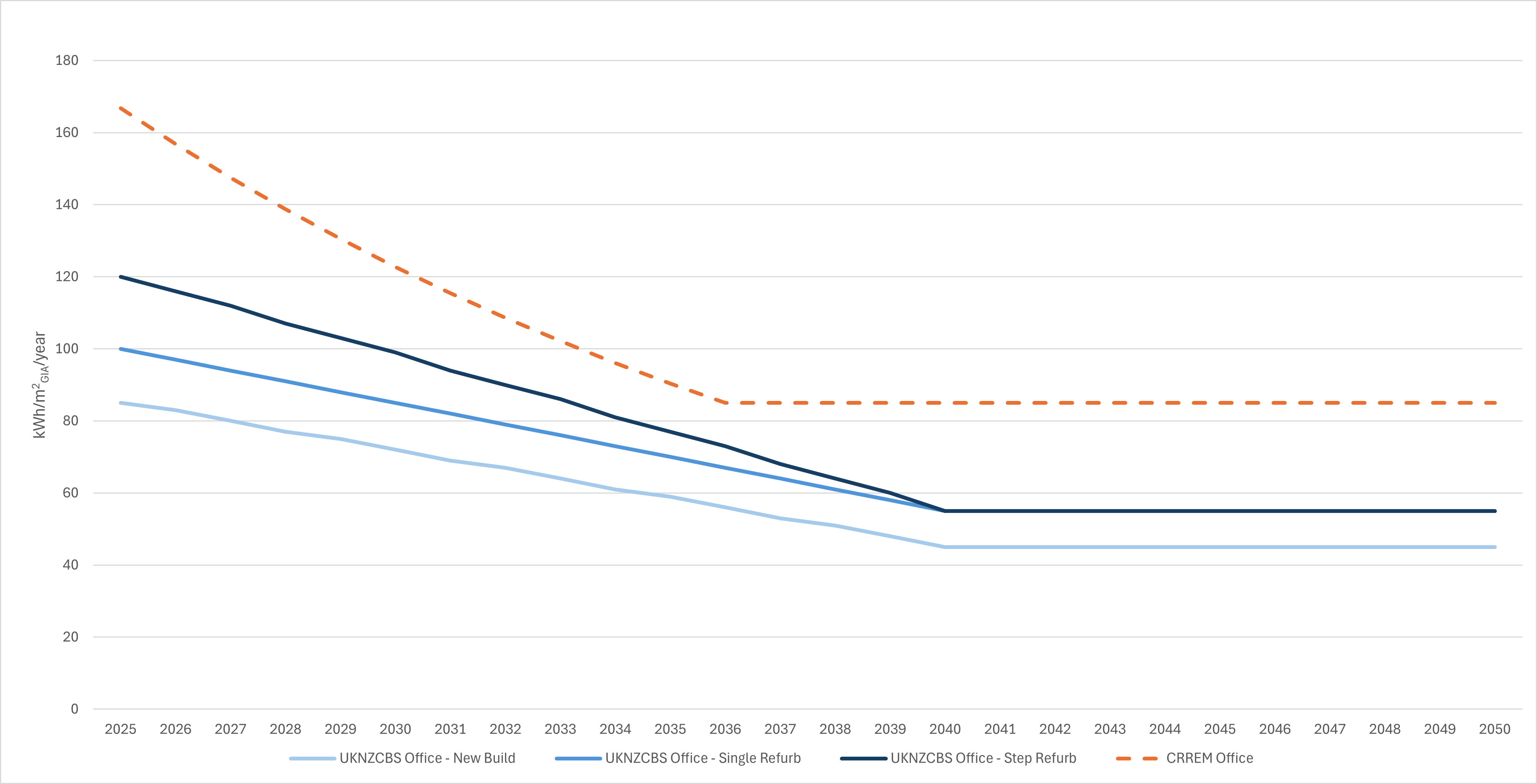

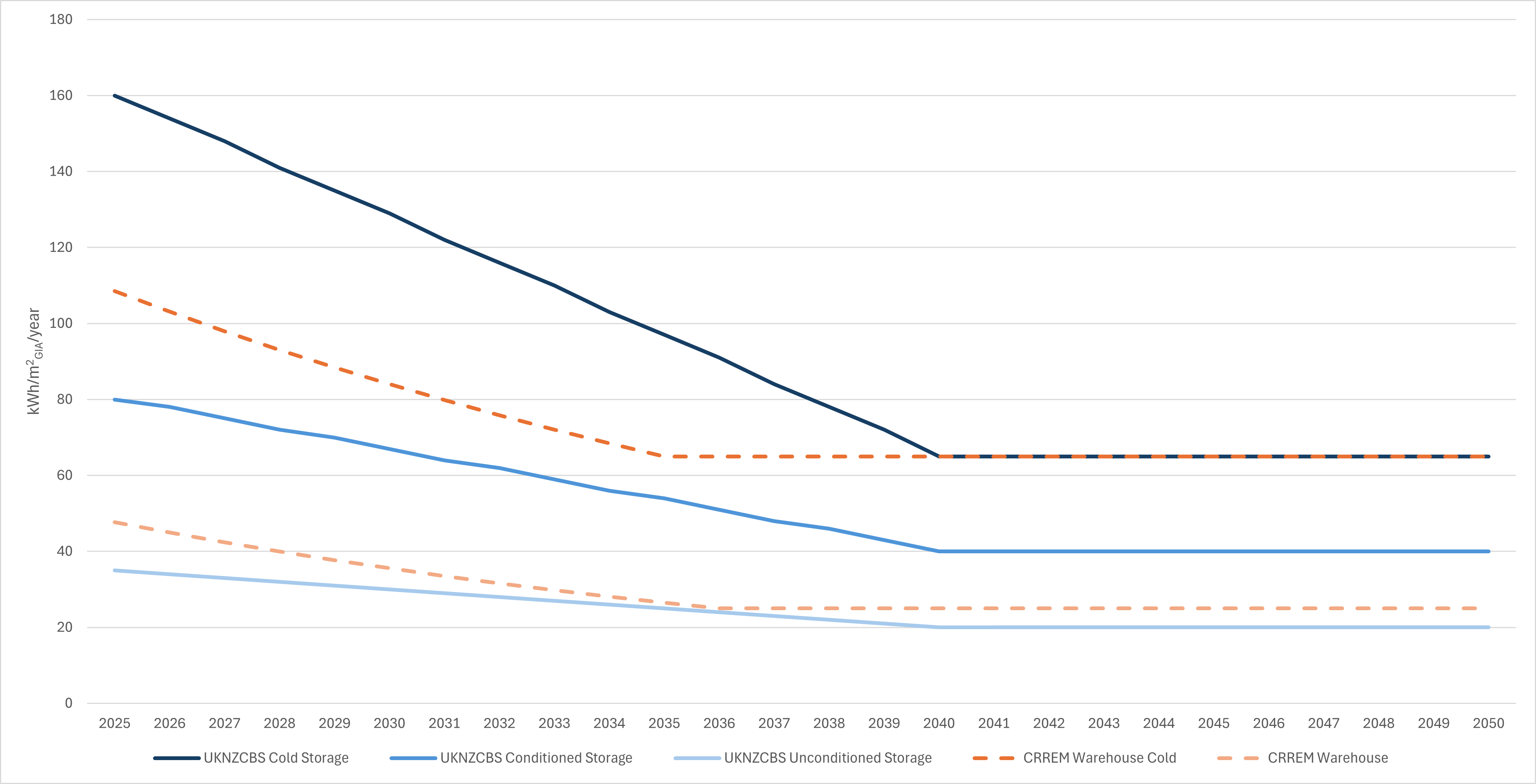

Of course, this cannot be the case if the imposed limits are too ambitious for most assets to meet. Another well-established assessment of operational performance, the Carbon Risk Real Estate Monitor (CRREM), uses a top-down national carbon budget approach to set Energy Use Intensity targets up until the year 2050. If these limits are not met for a given asset, it becomes ‘stranded’ – requiring investment in retrofit to realign the asset with a pathway to net-zero. Looking at how the UKNZCBS compares to CRREM’s targets we get the following:

Figure 2: UKNZCBS Energy Intensity limits vs. CRREM Energy Intensity Pathways[8] – Multi-residential

Figure 3: UKNZCBS Energy Intensity limits vs. CRREM Energy Intensity Pathways – Hotel

Figure 4: UKNZCBS Energy Intensity limits vs. CRREM Energy Intensity Pathways – Office

Figure 5: UKNZCBS Energy Intensity limits vs. CRREM Energy Intensity Pathways – Warehouse

As we can see, alignment alone with CRREM pathways is not sufficient, these must be exceeded (in some cases significantly) to be considered “Net-Zero”. Having such stringent requirements may risk deterring managers and owners from adopting such standards. Whether this rings true for the UK NZCBS remains to be seen, but as the standard is applied and tested, it will be interesting to see where these limits are fine-tuned, either relaxing or becoming more stringent following the initial pilot tests.

Ultimately, the standard brings forward a great deal of hard work defining what “best practice” looks like in the built environment, and what “Net-Zero” means. It is not meant to be a low-hanging fruit, nor is it supposed to be impossible to achieve. Real data has been used to form this baseline, and real data will continue to be used to inform how this standard evolves into the future.

It is now our role, as advisors, architects, engineers, developers, investors, and asset managers, to act on the NZCBS, and to test and refine it on real buildings. Making it foundational to all of our project work moving forward can ensure a lasting real-world impact from the many hours of research and collaboration that went into crafting this world-leading standard.

References

[1] Home | UK Net Zero Carbon Buildings Standard (nzcbuildings.co.uk)

[2] Better Buildings Partnership

[3] UKGBC – The UK Green Building Council

[4] Whole life carbon assessment (WLCA) for the built environment (rics.org)

[5] Home | UK Net Zero Carbon Buildings Standard (nzcbuildings.co.uk) 2024

[6] Buildings – Science Based Targets Initiative 2024

[7] Carbon Alignment | LETI 2021